Last Reviewed: 01 Aug 2025

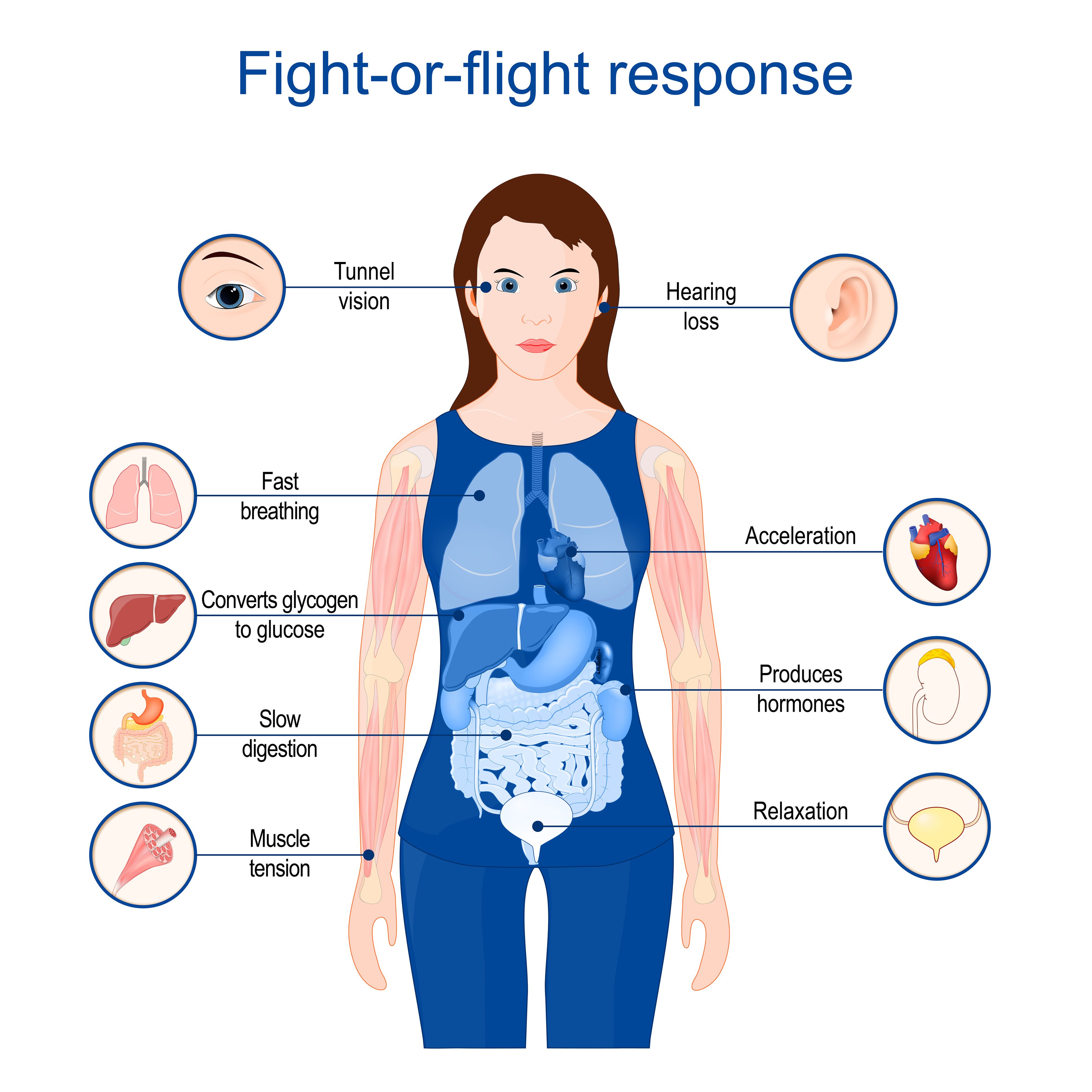

A stressful situation — whether something environmental, such as social eating, or psychological, such as persistent worry about whether you will like the next meal offered by your parents, can trigger a cascade of stress hormones that produce physiological changes. A stressful incident can make the heart pound and breathing quicken, muscles tense, and beads of sweat appear.

This combination of reactions to stress is also known as the “fight-or-flight” response because it evolved as a survival mechanism, enabling people and other mammals to react quickly to life- threatening situations. Such hormonal changes and physiological responses help someone to fight the threat off or flee to safety. Unfortunately, the body can also react this way to stressors that are not life-threatening, such as family difficulties, work pressures, or seeing some foods.

The image above shows how the body is affected during a fight-or-flight response. The body prioritises the larger organs of heart and lungs, senses become sharper and blood flows to the muscles and away from the digestive system in preparation to fight or run away. Therefore, no priority is given to eating or digestion, and so appetite decreases.

People who find themselves in high states of alert could experience extremely low appetites, sluggish bowels, constipation, or abdominal discomfort because of stress and anxiety. It is for this reason that we try to reduce stress associated with mealtimes and eating, because the presence of stress in a person with ARFID will only further inhibit their appetite and willingness to explore food. We are aiming for mealtime peace, including a calm transition to and from the table/meal to provide the individual with the ideal body state to enjoy food and mealtimes.

Create mealtime structure and predictability.

Use neutral language about food and eating such as ‘that is a strong flavour’.

Minimise noise and unwanted distractions from mealtimes.

Provide at least two preferred foods at mealtimes to increase willingness to attend the meal.

Cease all bribery, negotiation, and pressure placed on the individual with ARFID to try new foods.

Build trust with children - cease tricking them to eat food by hiding non-preferred foods in meals.

Resource - What is Anxiety?

https://www.beyondblue.org.au/mental-health/anxiety

Resources - Factsheets Blackdog Institute - Anxiety and Stress.

https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/resources-support/fact-sheets

© 2026 InsideOut

InsideOut acknowledges the tradition of custodianship and law of the Country on which the University of Sydney and Charles Perkins Centre campus stands. We pay our respects to those who have cared and continue to care for Country. We are committed to diversifying research and eliminating inequities and discrimination in healthcare. We welcome all people regardless of age, gender, race, size, sexuality, language, socioeconomic status, location or ability.