Last Reviewed: 01 Oct 2022

Diets are a recipe for failure! At least 75% of individuals who start a diet, will eventually regain the weight that they had lost (and more) (McEvedy et al, 2017; Saris, 2001; Anderson et al, 2001; Purcell et al, 2014). Many individuals conclude that they, not the diet, is the problem. This often leads to individuals attempting another diet, and therefore being stuck in the diet cycle.

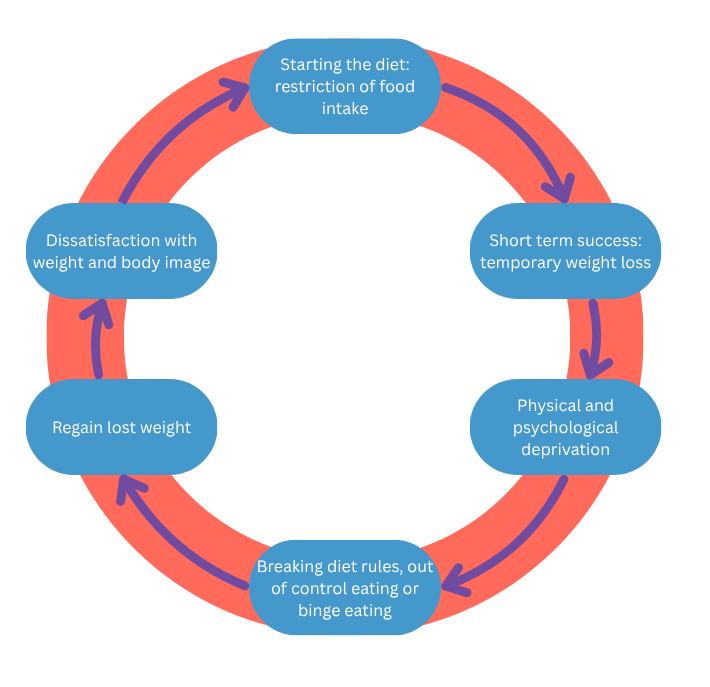

The diet cycle includes the following:

Losing weight seems like the solution for health, happiness, success, and to control body weight and shape, and so a diet begins. The diet is often prescriptive, quite inflexible and may involve counting kilojoules/calories, macronutrient tracking, weighing food, reducing portions, or cutting out food groups. The diet does not account for intuitive eating principles or hunger cues.

The diet is working! Individuals may notice changes in their body, weight and shape and feel successful and in control. This often reaffirms to the individual that they are unable to trust their body and follow their intuitive senses to eat normally, and that to continue to lose weight or maintain their weight loss, dieting needs to continue.

When we restrict what we eat, our bodies respond both physically and psychologically. Our metabolism begins to slow to conserve energy, hunger and appetite increases, and our mind becomes obsessed with thoughts about food and eating. Our bodies are working hard to push us towards breaking the diet so that our bodies receive the food it requires.

As our bodies are deprived of the food we need and want, breaking of the diet rules becomes inevitable. As a diet rule is broken, many individuals feel such guilt and disappointment in themselves, that they begin to break all of the diet rules and abandon the diet. This often leads to out of control eating and binge eating.

Regaining the lost weight

The eating that commonly follows breaking a diet rule is sometimes known as catch up eating and normally includes eating foods that weren’t part of the diet, eating when not hungry, and sometimes bingeing or out of control eating.

As a result, regaining the lost weight (and usually more) is most common. This leaves most individuals feeling that they have failed at the diet, and that next time if they can exert more willpower and self-control, they will succeed at dieting.

And thus, soon after, or maybe some time later, the cycle begins again.

References

Anderson, J. W., Konz, E. C., Frederich, R. C., & Wood, C. L. (2001). Long-term weight-Loss Maintenance: A Meta-Analysis of US Studies. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74(5), 579-84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579

McEvedy, S. M., Sullivan-Mort, G., McLean, S. A., Pascoe, M. C., & Paxton, S. J. (2017). Ineffectiveness of Commercial Weight-Loss Programs for Achieving Modest But Meaningful Weight Loss: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(12), 1614-1627. doi: 10.1177/1359105317705983

Purcell, K., Sumithran,P., Prendergast, L. A., Bouniu, c. J., Delbridge, E., & Proietto, J. (2014). The Effect of Rate of Weight Loss on Long-Term Weight Management: A Randomised Controlled Trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2(12), 954-962. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70200-1

Saris, W. H. (2001). Very-Low-Calorie Diets and Sustained Weight Loss. Obesity Research, 9(Suppl 4), 295S-301S. doi:10.1038/oby.2001.134

Tribole, E., & Resch, E. (2020). Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Anti-Diet Approach. New York: St. Martin’s Essentials.

On this page:

Subscribe to our newsletter!

© 2026 InsideOut

InsideOut acknowledges the tradition of custodianship and law of the Country on which the University of Sydney and Charles Perkins Centre campus stands. We pay our respects to those who have cared and continue to care for Country. We are committed to diversifying research and eliminating inequities and discrimination in healthcare. We welcome all people regardless of age, gender, race, size, sexuality, language, socioeconomic status, location or ability.